CHAPITRE 5a - Beaubassin

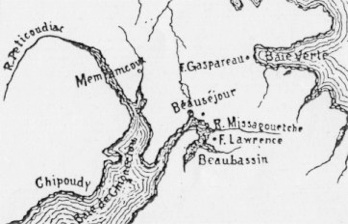

Beaubassin était un village en Acadie française fondé en 1671 situé sur l'isthme de Chignectou à proximité des marais salins de Tantramar aux abords de la rivière Mésagouèche. À l'époque, la région entière délimitée par les marais de Tantramar avait pour nom Beaubassin.5a01

Histoire

Jacques (Jacob) Bourgeois et Michel Leneuf de La Vallière et de Beaubassin fondèrent le village de Beaubassin en 1671 notant au passage la fertilité exceptionnelle des sols de la région marécageuse. Le village prend rapidement une importance stratégique puisque situé à la charnière de la péninsule acadienne et du reste du continent (sur l'isthme de Chignectou entre le Nouveau-Brunswick et la Nouvelle-Écosse actuels).

À la suite de la cession de l'Acadie à la Grande-Bretagne par le Traité d'Utrecht de 1713, les Français prennent l'initiative d'incendier le village et de forcer le déménagement des habitants du côté français. Les forces françaises se retirent et construisent en 1750, pour répondre à la construction sur l'autre rive de la rivière Missagouèche du Fort Lawrence par les Britanniques, le Fort Beauséjour. À la suite de la capture du Fort Beauséjour le 16 juin 1755 durant la guerre de Sept Ans, les Anglais décident d'occuper le nouveau fort qu'ils renomment « Fort Cumberland » après avoir incendié le Fort Lawrence pour éviter son occupation ultérieure par des troupes ennemies.5a01

Pour de plus ample information sur Beaubassin voir le site de wikipedia au https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beaubassin

Nous ajoutons ici le récit en anglais sur la tragedy des Acadiens de Beaubassin

CHAPITRE 5a.1 - Beaubassin And The Beginning Of The Acadian Tradegy

BY JOHN G. MCKAY 5a02

Amendment Expel/deport

All reference in this volume to the root terms expel and deport and their extensions will defer to deport as the operative term. With regard to the Acadian situation, they were deported rather than expelled since they had no choice of destination. The terms are not synonymous.

SECTION 5a.1.1 Preface

This volume is not intended as a comprehensive history of old Acadia, which, through the effort of many writers and historians, is well documented in the chronicles and archives of the province of Nova Scotia and could scarcely be accommodated in a work of this limited size. More specifically it is history centered on a small composite settlement that thrived in the remote northwestern district of Acadia during the latter 80 years of French tenure in the province. It is a sad history, although perhaps not more so than that of the other Acadian enclaves that thrived for more than a century and a quarter prior to "Le Grande Dérangement," in that the resurgence of the people in later times, and the re-establishment of their roots and culture in the old areas did not occur, could not have occurred at Beaubassin and its satellite settlements as it did in other areas. Its relatively short history speaks, nonetheless, of the effort and dedication of those who first established the Acadian presence in the Chignecto district, whose labour and dedication to the land made possible its subsequent, yes, eager occupancy by selected immigrants following the British conquest of North America. For this reason, and the fact that Beaubassin and many of the other settlements languished following the expulsion, those who returned after the deportation order was rescinded in 1764 were unable to regain their land. Inland a few hundred meters from the northeast shore of Cumberland Basin in Northern Nova Scotia, near the confluence of the Missaguash and LaPlanche rivers, lies the site of Beaubassin, the first Acadian settlement in the region of the Isthmus of Chignecto, the narrow neck of land that joined old Acadia of the 17th and 18th centuries to continental North America.

Decisions made in 18`" century Britain and New England as a result of the frequent French/English wars would lead to the ultimate confrontation in the contest for the ethnic dominance of the eastern regions of North America, but decisions emanating from individuals and cliques in New England and particularly British Nova Scotia affected the benign, peaceful Acadian inhabitants much more profoundly and, in the event, permanently than was the case involving the population of New France along the St. Lawrence River and farther into the interior.

In semi isolation from the mother country, Acadians in the small Bay of Fundy settlements, in contrast to the larger, more diverse and extensive centers along the St. Lawrence and westward, had for generations wrested a unique way of life from the tidal waters and salt marshlands along the bay shores, extending their presence into the smaller bays and river estuaries throughout old Acadia. Eighty four years after the first settlers arrived there, and nearly 125 years after the major influx of French colonists had re established the Bay of Fundy settlements in the 1630s, the village of Beaubassin and its satellite settlements in the Chignecto region literally passed out of existence. The farms and homesteads, the reclaimed marshlands, the cleared and cultivated land of the ridges and marsh enclaves following Le Grand Derangement began the slow, inexorable reversion to the natural state, as though nothing of the lives, the years of struggle and hope, had ever occurred. A time scale leading from Beaubassin's founding to its relative oblivion would be the equivalent of currently selecting all of the history, family records, community progress and optimistic outlook of any given modern community and, as far back as 1920, erasing it entirely, or secreting all evidence of its existence in scattered parish archives.

The new immigrants, brought in following the conquest and consolidation of the continent, came from different lands and developed different priorities from those of the Acadian settlers, who themselves differed as much from their British and New England successors as they had from their Canadian counterparts in New France. In effect, the Acadians were a unique people who had developed a unique culture by virtue of the type of land they chose to settle in the northeastern region of the New World.

Springing from the lowland districts in the valley of the Vienne River, a tributary of the Loire, and other riverine areas in west central France, the Roman Catholic majority of settlers were prompted to leave the old country to escape proscription following the religious wars that culminated in the 1616 Treaty of Loudon, which proved favorable to the Protestants. These peasant farmers, inured to the lowlands of the Loire basin in their home country where they were taught by the Dutch to drain and cultivate these fertile floodplains, were quick to recognize the potential of the salt marshes and tidal rivers of Acadia, while other European and Anglophone latecomers, unfamiliar with their methods would initially, and for decades thereafter, reject the marshes as essentially unproductive, except for the coarse, albeit nutritious salt marsh hay.

Nonetheless, following the Expulsion, when the vacant land was occupied by British sponsored immigrants, exiled Acadians who had made their way back to the region, were often called upon for advice regarding the pattern of construction for dykes and aboiteaux when the old structures began to break down for lack of maintenance by the uninformed English and New Englanders. Albeit carried out on a much larger scale in the modern era, no better method of salt marsh reclamation has ever been devised. Like the people of the Netherlands, who literally built their country on the floor of the North Sea, generations of Acadian families at Beaubassin and the Chignecto region wrested good land from the tempestuous Bay of Fundy waters in spite of the world's highest tides. The author is particularly indebted to Gill Collicott and Ralph Wightman, whose series: History Sketches appeared in the Amherst Citizen.

J.G.M. Amherst, 2003

SECTION 5a.2 Beaubassin

For nearly 83 years prior to the battle at Quebec's Plains of Abraham, where the ethnic, if not the political future of North America would be determined, an unassuming settlement of Acadian farmers had prospered in the Isthmus of Chignecto, the westernmost region and politically contentious area of old Acadia.

Having been investigated in 1612, but only marginally explored at that time, the Chignecto region comprises the narrow neck of land 18 miles in width and approximately 350 square miles in area that connects the province of Nova Scotia to continental Canada.

Seen from the great loop of the basin at the northeast head of Bay Françoise later named the Bay of Fundy, the land presented a panorama of forested uplands and immense grassy marshlands set amidst a grand solitude described by the first explorers as ". . .one great pasture."

What the explorers from the settlement at Port Royal were viewing were the great salt marshlands comprising about a third of the isthmus in the northwest southwest quadrant, and the interspersed upland ridges that divide the lowland marshes into separate tracts. They undoubtedly saw as well the estuaries of the rivers draining the marshes in the immediate area of the basin, which would later be named the Tantramar, in the west, the Aulac, Missaguash and LaPlanche in the north and east, and the Maccan/River Hebert estuary in the south. Farther west, branching from Shepody Bay, are the Shepody, Memramcook and Petticodiac Rivers, which would all play a role in the progressive settlement of the region. Despite the area's apparent appeal, it would be another 60 years before people from the overcrowded older settlement would arrive on the shore of the turbid basin with the intention of settling the area.

The first six families, led by Jacques Bourgeois, went ashore in 1671 at a place where one of the upland ridges came nearest the water, where the common exit channel of the two rivers later named Missaguash and LaPlanche drain the marshes on either side of the ridge. This river outlet permitted access between the shore and the curving channel of the basin at all stages of the tide except dead low water, when the estuary would be empty of all but the shallow freshwater outflow.

Almost directly onshore at this place the land consisted of a stretch of gently sloping ground rising above the Missaguash riverbank on the northwest and the dead flat marshes to the south. The relatively high land ran back north eastward from the river confluence to the toe of the ridge, about 4,000 feet distant, that commanded a view of the marshes on either side. Farther to the south, two and a half miles across the marsh, another ridge, parallel to the first, also ran east into the forested region beyond the open marsh, its western end diminishing to low, sprawling upland that swung round to the south toward the Nappan and Maccan rivers. On the other side of the Missaguash, two miles westward, another ridge began at a high promontory above the sloping basin shore. This ridge, too, ran back northeastward until it met the forested area beyond the upper marshes.

Through the interior of the isthmus, from the marshes to the salt water bay, later named Baie Verte, opening on the Gulf of St. Lawrence, the land ranged between virgin forest and low bog land, moose pasture and caribou plain, with dry rolling woodland and clear, gently flowing streams in the east, all rich in wildlife amidst a vast solitude that had lain undisturbed by mankind over the millennia since the retreat of the glacial ice-except for the random footpaths of the indigenous natives who, it appears, visited the area on a seasonal basis to take advantage of the abundant fish, wildfowl and game in their season.

Jacques Bourgeois, the ostensible leader of the initial group of settlers, came to Acadia as a surgeon in 1642 during the governorship of Charles d'Aulnay, and married Jeanne Trahan shortly after arriving. Jeanne was the daughter of Guillaume Trahan, a toolmaker who had sailed from Bayonne with Claude de Razilly and seven other families aboard the Saint Jehan on 1 April 1636. Bourgeois later rose to the rank of Lieutenant in the small French garrison at Port Royal at the time of its surrender to the English, in 1654. At that time there were perhaps 250 people in all of Acadia and evidently they posed no apparent threat to the English, who neither brought in settlers of their own choosing nor established a garrison in the colony, earlier named Nova Scotia by Sir William Alexander, Governor in 1621.

Perhaps as a consequence of having seen the earlier report regarding the Chignecto region, and possibly believing that in its splendid isolation the remote area offered a better measure of security from New England raiders and the on again, off again French English conflicts that had plagued the colony almost from its inception, Bourgeois and five other families, including his sons, Germaine and Guillaume, his sons in law, Pierre Cyr and Germaine Girouard and their families, embarked in 1671 for the "Great Pastures" of Chignecto, at the head of Bay Françoise, on the northeast shore of the upper basin.

At the location of the small, focal settlement, established on the gently rising ground southwest of the ridge, the principal attraction was undoubtedly the naturally cleared grassland of the adjacent marshes. It would soon become apparent, as it had in the salt-marsh settlements down the bay, that their initial encampment must necessarily be established on ground that lay above the range of tidal inundation into the marshes proper during the spring phase of the tide cycle. It would also become apparent, based on experience gained, that dyking of the estuarine shores and the isolation of marsh enclaves by other dykes would be required before the full benefit of the grassland could be realized. Thus, over the next 77 years, the village grew to sprawl across the ridge and along its flanks, with outpost settlements established at similar riverine sites throughout the region.

The land on which the village was established begins at a low hillock above the confluence of the two rivers, and gradually extends eastward and across the toe of the ridge, with the church and graveyard overlooking the slightly lower ground to the west. Over time the dwellings and cleared land extended farther eastward along the uplands overlooking the marshes in the northwest and south. During that time dykes were constructed and the various marsh enclaves on both sides of the ridge were isolated from tidal inundation. This latter was accomplished by incorporating wooden sluice gate arrangements into the construction of the dykes. These, known as aboiteaux, were inserted beneath the dykes where they crossed natural streams or rills, or where drainage ditches were dug to collect the runoff water. An aboiteau permitted the egress of this fresh water from the land during low tide, while the current actuated gate blocked the influx of salt water when the tide rose above the level of the marshes.

In keeping with the French seigniorial system of land control, the governor of New France, Richelieu, granted to Michel Leneuf de La Vallière de Beaubassin an initial seigneory of ten square leagues (90 square miles), in 1676. This grant would eventually encompass all of the territory in the Chignecto region. La Vallière's letters patent stated that he was not to interfere with the settlers already established there, or infringe upon any other land they might acquire or develop. Perhaps as a way of remaining aloof from his tenants, La Vallière established himself on the north side of the Missaguash River on a sprawling hillock or glacial drumlin rising in the marshes between the river and the next ridge to westward. He named the hillock Isle Vallière, later to be renamed Tonge's Island. Here La Vallière erected a palisade around his buildings and dyked some of the basin shore below the western slopes of the hillock to protect the surrounding marshes. He also named both the offshore basin and the new settlement across the river Beaubassin.

Legend has it that La Vallière named the nearby river the Marguerite after his young daughter in whom he held high expectation with regard to her marrying into the influential families of New France, at Quebec or Montreal. After she had settled on a lesser individual named De Gannes as the husband of her choice, her disappointed father had renamed the river the Missaguash, which is a phonetic interpretation of the Aboriginal word Mesagoueche, their name for the ubiquitous muskrat inhabiting the marshes.

Over the following 25 years the settlement prospered, and under Jacques Bourgeois' leadership more land was cleared along the ridge as the village expanded. In the meantime Beaubassin village acted as a base from which to establish satellite settlements throughout the isthmus, notably those on the ridges to the northwest and south-which, although considered part of Beaubassin in the broader sense, would be nominally called Weskak (present day Westcock), Pré des Bourgs (Sackville), Pré des Richards (Middle Sackville), Tintamare (Upper Sackville), La Butte, Le Coupe and Le Lac on the Jolicoeur Ridge, and Portage, at the head of the Missaguash. Menoudie (Minudie), and the Elysian Fields, Maccan (Makon), Nappan (Nepane), and River Hebert, all located along the riverine end of the basin, to the south of the main village, were also settled; as well as the older Beaubassin lands along the Missaguash and LaPlanche rivers the land on the nearby ridge south of the latter river had been sparsely settled in 1694.

Not many new settlers arrived in Chignecto before 1686, perhaps because of La Vallière's policies. A 1682 list of 11 men at Beaubassin who refused to accept the concessionary privilege included Pierre Morin, Guyou Chiasson, Michel Poirier, Roger Kessy, Claude Du Gast, Germaine and Guillaume Bourgeois (Jacques' sons), Germaine Girouard (Jacques' son in law), Jean Aubin Migneaux, Jacques Belou, and Thomas Cormier. As a consequence, La Vallière was forced to bring in indentured farmers from outside Acadia to increase the manpower, thus ensuring the progress of such community-oriented tasks as dyke building and the construction of mills and aboiteaux. At least one of these bonded men married an Acadian girl.

Cattle, hogs and sheep were the stock of choice for the peasant farmers. The forests teemed with moose and woodland caribou, and snowshoe hares and partridge were in abundance. Legions of waterfowl fed and nested in the marshes, while each spring the rivers saw the influx of great shoals of the pelagic Gaspereau on their spawning run inland to the fresh water lakes beyond the reach of the tide, some four miles up the marshes and beyond.

When cultivated the marshland was found to be extremely fertile following two or three fallow years to allow excess salt to be flushed away in the fresh water runoff behind the protective dykes, and good crops of wheat, flax and corn were grown, as well as kitchen vegetables. Both La Vallière and Jacques Bourgeois constructed gristmills, and Bourgeois also operated a sawmill. The record does not appear to indicate what mode of power was used to operate these mills. A small creek, currently named King Creek, to the west of Tonge's Island may have lent itself to the construction of a dam and spillway, but not without some dyking to protect the mill site from tidal inundation. South of the Missaguash a nearby power source for Beaubassin village may have been established on what is now Gordon's brook somewhere upstream from its junction with the LaPlanche River. Nonetheless, with the extreme tidal range in the rivers resulting in nearly zero water in the estuary at low tide, to 35 feet at high tide, as well as the reversing flow of the current, construction of mill wheel facilities would require preserving a head of water upstream of the mill site, which could then be utilized through a flume or spillway at low tide.

There were several non tidal streams or seasonal rills flowing out of the uplands along the north slopes at LaPlanches, or what would become the Amherst Ridge, two and a half miles to the south of Beaubassin village. One brook in particular that flowed out of the western end of that ridge was a good potential source of waterpower, and has been so used into the modern era. The source branches of the Tidnish River, rising some eleven and a half miles across the isthmus and flowing eastward into Baie Verte, also offered good mill sites except for their distance from the village. Three small streams also flowed into the head of the LaPlanche marsh east of the Amherst ridge, beyond tidewater; but again, isolation and a lack of adequate roads during the early years would have made them virtually inaccessible as potential mill sites. In the circumstances, there is no evidence that these streams, other than possibly the brook at the western end of the Amherst ridge, were dammed during the Acadian years.

By 1698, 27 years after its founding, there were 28 families living in Beaubassin. The census for that year shows that Jacques Bourgeois was 82, and Jeanne was 72. Their son, Germaine, was 48, and his wife, Madeleine (Dugas) was 34. Their two children, Guillaume and Agnes, were 24 and 12 years of age. The extended family had 22 cattle, 15 hogs, and 30 acres under cultivation; they owned three guns, and kept one servant.

The 28 families living in the settlement at that time were made up of 21 surnames, with intermarriages between these families as well as wives of an additional nine family surnames, for a total of 178 individuals. Between them they possessed 352 cattle, 176 sheep, 160 hogs, 32 fruit trees, and had a total of 450 acres under cultivation. There were 26 guns in the settlement, and three servants.

Surnames making up the principal families were: Arseneault, Bernard, Blou, Boudrot, Bourg, Bourgeois, Chiasson, Chastillon, Cormier, Devaux, Doucet, Girouard, Godin, Godet, Guercy, Hache, Mercier, Mirande, Poirier and Richard. Wives who married into these families were from other families in the scattered settlements: Blanchard, Cyr, Dugas, Guerin, LeBlanc, Martin, Melanson, Pellerin and Trahan.

The disposition of the people, and the material holdings of the Beaubassin district that was indicated in the census might seem remarkable in light of the raid in the fall of 1696 by Boston based Colonel Benjamin Church, during which he burned most of the original village to the ground. Church was a puritanical enemy of hostile Indians and the French, and would make at least five excursions to pillage the Acadians, and would return to Beaubassin again in 1704.

Jacques Bourgeois died at Port Royal in 1701. He had lived to see the Beaubassin settlements well established if not altogether secure over the past 30 years. He saw his sons prospering on the virgin land they had wrested together from the wilderness, and had watched his cattle grazing in the marshes made safe from tidal incursion by virtue of his labour. He had eaten the bread that Jeanne made using flour milled from his grain in his own gristmill. In the fiercely devout Roman Catholic faith that the Acadians adhered to, Sieur Jacques Bourgeois probably died content with his lot. While there had been labour and hardship, periods of apprehension and the terror of New England raiders during his nearly 60 years in Acadia, both at Port Royal and Beaubassin, his legacy would endure for another half century along the slopes of the ridge, sunlit in the warmth of summer and chilled in the wind blasted depths of winter, embodied in the lives of kith and kin, until the fatal clouds gathered and the once and final storm was unleashed upon the fair Beaubassin and all of its unique, God fearing populace.

Of the dark circumstances to affect the destiny of the little settlement at Chignecto during the new century, perhaps none would be as decisive as the Treaty of Utrecht that, in 1713, saw France cede to the British crown Hudson Bay, Newfoundland and most of Acadia, while retaining Isle Royale (Cape Breton) and Isle Saint Jean (Prince Edward Island). These eastern concessions, won or manipulated by old country factions, should have had no bearing upon the existence of the St. Lawrence River colony and those farther into the interior, as determined in the collective mind of officials in New France. The British came to develop other views.

For the Acadians, on the other hand, in all of the uncertainties of the past that were wrought by British claims and French concessions, the boundaries of old Acadia had never seriously entered into the equation beyond assumptions by both sides. What had not been specifically defined as part of Acadia the wilderness territory comprising the present day province of New Brunswick and parts of the State of Maine was assumed by the French to belong, nonetheless, to New France, a hypothesis based on the fact that the boundaries had not been in serious contention with regard to past treaties.

Again, with this new treaty, the boundaries remained at best ill defined, allowing both sides to take advantage of what had not been spelled out in this latest conciliatory rag. As the 18th century wore on, this discrepancy would come to plague the Acadians in general, and those in the Chignecto settlements in particular.

In time it appeared that New France was at least temporarily willing to accept the loss of sovereignty over old Acadia, if not the loyalty of the people. Although the Acadians in Chignecto were, like their cousins in the rest of old Acadia, valued as producers and purveyors of supplies and material among other French colonists and the New Englanders, their productivity would never be more important than it became when the decision was taken to construct fortress Louisbourg on Isle Royal as security against British naval incursion into the St. Lawrence River, the front door to the interior French colony.

Another eventuality destined to profoundly if not fatally affect the population of Beaubassin and surrounding district would be the emergence of the enigmatic priest Abbe Jean Louis LeLoutre, an avowed hater of the English, supporter of the French monarchy and missionary to the Mi'kmaq, the latter providing him with a certain manipulative power over the generally benign, easily corrupted aborigines.

Jean Louis was born at Morlaix, in Brittany, France, on 26 September 1709. His mother died when he was seven, and his father when he was 11, after which he went with his four brothers and a sister to live with his mother's family. Raised in relative affluence and deeply religious, he aspired to the priesthood at an early age, and at 21 entered the Ste. Esprit seminary, in Paris. By March 1737, having changed his vocation, he graduated from the Seminaire des Missions Etrangeres (foreign missions) and promptly embarked for service in Acadia, ostensibly to replace the pastor at Annapolis Royal, who had had a falling out with the Lieutenant Governor. By this time of course Acadia was again under British control, and Louisbourg had been established on Isle Royale since 1720. Arriving at the fortress town in August 1737, the 28 year old LeLoutre found that reconciliation had taken place between the pastor, M. de Saint Poncy, and Lieutenant Governor Armstrong, and that the pastor's position was no longer open to him.

Having been assigned then to the interior Mi'kmaq mission at Shubenacadie, which had been without a priest for 12 years, LeLoutre remained in Louisbourg for the next ten months studying the Mi'kmaq language, utilizing in that endeavour the native alphabet perfected by Abbe Pierre Maillard of the mission at Port Toulouse on Isle Royal. Over the next seven years LeLoutre became well established as a principal spiritual leader of the Christian natives living in Acadia. He traveled extensively, serving both as priest to the Acadians and missionary to the Mi'kmaq.

Among the Acadians, particularly those generations born in North America, literacy and formal education were rarities indeed, being somewhat low in the list of priorities of a populace largely wedded to the land. Being generally ignorant of English law, if not its French counterpart, the people looked to their priests for guidance in legal as well as spiritual matters. Among the ignorant and highly superstitious Mi'kmaq as well who, for the most part, had been converted over the past century the presence of the young, highly educated priest, one particularly adept in the coercive methods of the church, was a dominant presence indeed.

LeLoutre left Isle Royal in September 1738, crossing to the mainland and moving up to Tatamagouche, thence crossing through the virgin wilderness to the Shubenacadie River in company with his Indian guides, and arriving at his destination in early October. The mission, which would serve as his headquarters, had been established a few miles upstream from the confluence of the Shubenacadie and Stewiacke rivers. In the absence of roads, the Shubenacadie was perhaps the most travelled waterway in the central region. Going north from the mission for some 20 miles downstream, a well paddled canoe taking advantage of the current, and catching the right stage of the tide, could be in Cobequid Bay by low water. Also from the mission, a 35 mile journey southeast, through an interconnecting system of streams and lakes traversing unimaginably pristine forests could bring a traveller to Chebucto, on the Atlantic coast. A few more years would see the founding of Halifax at this site.

LeLoutre had his first brush with British authority when he failed to pay his compliments to the governor and obtain a license for his long neglected mission, which was only attainable at Annapolis Royal. The matter was soon resolved, and LeLoutre remained ostensibly on cordial terms with the authorities, at least until 1744.

Whatever ill feeling LeLoutre may have nurtured toward the English at the outset of his mission, it was clear from his activity during the abortive French attempt to capture Fort Anne at Annapolis Royal, in September of that year, where his loyalties lay. With the encouragement of the governor of Louisbourg and Abbe Maillard, the Indians friendly to the French routinely assisted the military authorities by raiding into areas of British control, and no one would be better suited to relay that encouragement than LeLoutre, who used the same tactics in rallying the superficially Christian Indians that he would later use against the devout Acadians at Beaubassin and elsewhere: the threat to deny them the sacraments of the church, not to mention withholding cash payment to the Indians for English scalps.

Also in 1744, with the outbreak of the War of the Austrian Succession, Britain and France were once again at one another's throat. Never satisfied with the relative peace obtaining in North America, both sides encouraged their New World counterparts to raid into the enemy enclaves. Thus LeLoutre became so heavily involved with the French cause that his notoriety (among the English) and his value (to the French) in rallying the Indians became well known throughout New France.

Early in the following year, in keeping with the opening of general hostilities, Quebec dispatched an armed force through the wilderness via Chignecto with the intention of re capturing Annapolis Royal. The attempt was once again thwarted. This time by the attack on Louisbourg by a 4,000 man sea borne force from New England under William Pepperell, who managed to seize the fortress.

LeLoutre and his Indians undoubtedly accompanied the French force attacking Annapolis Royal, and when that group were suddenly diverted to the defence of Louisbourg, under siege by the New Englanders, LeLoutre's band were with the military force during their attempt to cross the strait at Canseau. From this time onward, and at LeLoutre's direction, the Indians were involved with clandestine activity and ambuscade throughout the region, continuing for the remainder of that unsettled period.

With a price on his head, LeLoutre felt it expedient to flee the territory, at least temporarily, and on 24 September 1745 arrived at Quebec, accompanied by five Indians. A week later he departed with specific instructions governing his future activity among the Acadians. In effect, his priestly duties had now been extended beyond spiritual guidance to quasi military leadership.

During the summer of 1746, from his mission chapel on the Shubenacadie, and again with the assistance of his Indians, LeLoutre was involved in relaying intelligence communications between the French naval force at Chebucto and the French regulars from Quebec gathering at Chignecto. The question of sovereignty in Acadia was fast entering the forefront of British determination, which had seen little in the way of consolidation and genuine enforcement of their command during the thirty odd years that had elapsed since the Treaty of Utrecht had declared old Acadia a British colony albeit, at the time, sans colonists.

In 1749, by way of bolstering their tenure, following nearly forty years of relative indifference to the Acadian presence, if not that of the French military, the British established a permanent garrison at Chebucto, which was re named Halifax. Within the year the garrison there had constructed two forts surrounded by stockades, including Fort George on the high ground that would become known as Citadel Hill. During the first year the settlement was surrounded with a rough barricade of logs, brush and stumps, to be replaced the following year with a log palisade and line of defenses. In 1750 they turned their attention to George's Island, inside the harbor entrance, which by November was fitted up with seven heavy guns with a palisade surrounding them. Then as now the harbor and basin was capable of sheltering and protecting the entire Northwest Atlantic Squadron if need be, and effectively denied French ships the freedom to supply Louisbourg with provisions carried overland to Chebucto from the Chignecto region via Cobequid Bay and the river route cited above.

It should be noted that except for a few British families at Annapolis Royal, and a few others who resided at Canseau on a seasonal basis to partake of the fishery, all of the civilian residents of Nova Scotia were Acadian, upwards of 10,000 of them. As well, there were no permanent French military garrisons anywhere in peninsular Nova Scotia. Perhaps more imposing upon the observation of the Acadians than the establishment of British settlers at the time was the protracted construction of blockhouses and strategically located bastions, both as a defense of Halifax itself, and other areas frequented by the Acadians, particularly along the long established inland routes. Certainly the beginning of this work, following the arrival of Edward Cornwallis, signaled the British intention to finally claim rigid sovereignty over old Acadia, as prescribed in the Treaty of Utrecht.

As early as September 1749 a detachment under Edward How constructed Fort Sackville as a hedge against incursion into Bedford Basin at the eastern end of the overland trail. This fort was of particular importance in that the Sackville River was a traditional route of the Indians in their passage through the interior to the sea. It also commanded the Minas Road, cut through earlier by the Acadians for driving livestock and carrying provisions for transport to Louisbourg from Chebucto. Eventually perimeter blockhouses were constructed, along with the road across the narrowest part of the Halifax peninsula, thus closing the back door to the harbor from attack.

To consolidate the English hold over the country generally, Captain John Handfield of the garrison at Annapolis Royal was ordered to establish a strongpoint at Minas, and by November 1749 had constructed a picketed fort and a blockhouse. As well, a detachment under Captain St. Loe was ordered to establish positions on the western side of the Piziquid River, near the present day Falmouth. Fort Edward, on the western side-present day Windsor-was built in the early summer of 1750.

Of course it was abundantly clear to the French, if not the Acadians, that the British were openly demonstrating their intention to claim sovereignty over the territory. What was not entirely obvious was whether or not the British would honor the boundaries established by the Treaty of Utrecht some 35 years before. There is little doubt that by this time the French were feeling the pressure of the growing population imbalance between New France and the more climactically hospitable English colonies to the south-a ratio in the order of 20 to 1. Nonetheless they, too, were determined to establish autonomy over what they considered rightly French territory, from the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys to the westernmost boundary of old Acadia, wherever that line was deemed to lie.

In view of the increased British defensive construction taking place throughout peninsular Nova Scotia, a detachment of French regular troops supported by Canadian militia and led by Chevalier de La Come was dispatched from Quebec to liaise with an earlier detachment led by one Boishébert. While Boishébert constructed a fort at the mouth of the Saint John River, La Come was instructed to hold Chignecto and prevent the British from establishing themselves north of the Missiguash River. As a consequence, directly upon arriving in the fall of 1749, after linking up with Boishébert's detachment, de La Come moved to the easily defended Pointe Beausejour, on the western promontory of the ridge north of Beaubassin, overlooking the Missaguash marsh.

Protests were launched by both sides, resulting in English authorities dispatching Captain John Rous to intercept French supply vessels bound for the Saint John post, and to order Boishébert away from the site. In reprisal the French ordered the capture of English vessels trading at Louisbourg. Crucial to rounding out British determination, and certainly ominous in regard to the continuing existence of the Acadians in the Chignecto region, was the decision to establish a fort on the south side of the Missaguash River, a task that was undertaken by Major Charles Lawrence in 1750.

On 20 April, Lawrence, having departed Minas with a force of 400 men, lay at anchor down the basin from Beaubassin. In the meantime Chevalier de La Come, whose headquarters had been on the east side of the Memramcook River, was now at Pointe Beausejour, barely two miles across the open marsh from Beaubassin. It would appear from his correspondence that Governor Cornwallis, in dispatching Lawrence to Chignecto, was somewhat uncertain whether or not the French had indeed erected a fort in the region, and also seemed contemptuous of any French claim of sovereignty north of the Missaguash in that he instructed Lawrence to "erase" any fort found at Chipoudy, which was far outside the Missaguash River boundary. Cornwallis was only aware that a French fort was planned and perhaps had been built "somewhere thereabouts," and had instructed Lawrence to destroy it.

As well as demonstrating the British claim to at least all land south and east of the Missaguash, Lawrence's fort would also counter French protection of the overland route from the headwaters of the Bay of Fundy to Baie Verte, across the isthmus, and stand against French incursion south of the river. During this period of relative peace, supplies for the garrison at Louisbourg had continued as usual to flow through the Chignecto region from the settlements farther down the bay, for despite the uneasy relationship between the people and the British military, their countries were not at war.

News of Lawrence's imminent arrival had preceded him following the expedition's departure from Halifax on 5 April, with their partly overland and partly waterborne journey taking some 15 days. Of course as soon as their final destination became apparent, it would be quickly relayed to Chignecto in the van of the group. Whether or not British intentions were already known or anticipated, as early as January Abbe LeLoutre, with the backing of his Indians, had proclaimed from the steps of the church of Notre Dame L'Assomption, at Beaubassin, that Acadians trading with the English would be harshly dealt with and that there could be no alternative to removing from their traditional land to the vicinity of Pointe Beausejour, northwest of the river. As a conciliatory measure, and in the name of the governor of New France, he promised that upon re settlement throughout the new district the people would be supported for three years and even indemnified for any losses incurred by their removal. To further allay their reluctance, he threatened them with abandonment by their priests and the withholding of the sacraments. In their deeply held Catholicism it is difficult to assess whether the latter promise or the threat of allowing the Indians to lay waste their property and carry off their wives should they choose to remain on their farms held the greater terror for them.

Lawrence, in the Albany, had with him a man by the name of Landry, from Minas, whom he intended to use as a deputy, sending him ashore bearing a letter and proclamation from Governor Cornwallis to the people of Beaubassin. Lawrence also expected Acadian deputies to come aboard to receive a statement of his aims and objectives. Although those aboard the English vessels had been aware throughout the morning of a pall of smoke hanging over the village site, it wasn't until Captain Cobb returned from delivering Landry ashore, that they learned that most of the lower village had been burned to ashes.

Since neither Landry nor the Beaubassin deputies had returned with Cobb, it was assumed that cooperation would not be forthcoming from the inhabitants. As a consequence the transport vessels were ordered to move to the upper basin, nearer to an appropriate landing site, which was done the following morning.

Upon arriving off Beaubassin, Lawrence saw that much of the main village had been burned and that the people were in the process of removing themselves, their chattels and livestock to the uplands north of the river.

At high tide the troops were landed at the confluence of the rivers and assembled on the rising ground immediately west of the village. In a short time the British were approached by a group of civilians bearing a white flag, which was accepted as a flag of truce. Major Lawrence dispatched Captain Scott to interview the group from whom he learned that they were to use the flag to mark the boundary of French territory. They also informed Scott that they knew nothing of Landry or of Lawrence's letter, and that an officer would be sent from M. de la Come at Pointe Beausejour to confer with the British. At the approach of the officer and his party, Lawrence again dispatched Captain Scott with a message to de la Come ordering him, as per Cornwallis's instructions, to retire immediately from British territory or be treated as a public incendiary in view of the burned village, which lay in recognized British territory. In fact, it was Abbe LeLoutre, who had moved his headquarters to Chignecto out of the English dominated interior at the Shubenacadie mission, whose Indians had burned the village, forcing the exodus of the habitants to the north side of the river.

Later, as the British attempted to advance farther inland, they found themselves challenged by a force of armed Acadians and numerous Indians who had been goaded into assuming a defensive stance by LeLoutre. This group, arrayed behind the dyke near the Missaguash River, seemed intent upon challenging the British. In the meantime, de la Come had sent a message to Lawrence requesting a meeting, which was granted. While the two groups faced each other across the river, Lawrence told de la Come why he was there, to construct a fort in British territory, and that according to British authorities the French status in the region was incorrectly assumed and that their action in constructing a fort, which they were yet to do, was intolerable. He reiterated as well that since the inhabitants of Beaubassin had been threatened in order to make them retire across the river, and in view of their unsown land and the burning of their dwellings, he could be treated as a public incendiary. De la Come could only respond by saying that he was acting upon the orders of the Governor of New France.

At the conclusion of the interview it was determined by Lawrence and his staff that the hostile force was well ensconced behind the dykes, and that while he was capable of defending his situation, and had in effect been ordered by Cornwallis to endeavor to reduce any French defensive works he encountered, he concluded that his best option for the time being was withdrawal. As the British force embarked it was seen that the remainder of the buildings in Beaubassin village were in flames.

Not to be thwarted by the unexpected resistance, Major Lawrence retired with his force to Minas, still determined to carry out his orders. Returning to Beaubassin in September with a force and provisions ample for the task, Fort Lawrence was hastily constructed above the toe of the ridge overlooking the charred and abandoned ruins of Beaubassin village.

Nonetheless, work on the fort was not without its dangers, the party being constantly harassed during the construction, chiefly by LeLoutre and his Indians who, even during the English attempt at landing, laid down musket fire from behind the dyke at the confluence of the two rivers. The English sent an armed schooner up the LaPlanche River on the high tide to outflank the Indians. By virtue of the peculiar layout of the dyke along the estuary, a vessel could penetrate sufficiently far upstream to place it in a position to fire behind the dyke. LeLoutre and his party then retreated eastward, taking up positions behind the low wall of the village cemetery and continued a sporadic fire during the disembarkation of the English force. Although harassment of the English continued throughout the construction period, by early October the fort was ready for occupancy.

Little doubt exists regarding the inhabitants' extreme reluctance to destroy their villages and remove to an uncertain situation across the river, but move they did at LeLoutre's command or more precisely, under his threat to withhold the sacraments and have his Indians loosed upon them. On 23 September, while English activity at Fort Lawrence was still proceeding apace, the families from south of the river, their men already at Pointe Beausejour, crossed the Missaguash, leaving their homes and belongings to be burned by the Indians. In the course of events, the inhabitants were all on the north side of the river and the villages entirely abandoned and destroyed by the time Fort Lawrence was completed.

In the event, driving their livestock before them, a total of 830 people, including children, vacated these satellite settlements, being perhaps the only Acadians sufficiently close to the dubious boundary to actually leave old Acadia for the ostensible security north and west of the Missaguash. In any case, it was not the English who had forced this exodus, and the peoples' compliance is moot evidence of their fear of, or respect for authority, particularly that of the church and its agents.

The emergence of Charles Lawrence, and his humiliation at Chignecto in April, can be categorized as the third and most ominous in the sequence of fateful circumstances destined to resolve the future of the Acadians. In effect, the 1713 treaty had made them subjects of the English king. LeLoutre and his Indians the latter at least marginally embracing the Roman Catholic faith had become a thorn in the English side during the ostensibly peaceful period of the 1740s, and the Acadians, whether threatened and coerced by the priest to participate in his mischief or not, had steadfastly attempted to negotiate unacceptable conditions with regard to the oath of allegiance required of all foreign subjects occupying British lands.

Major Lawrence, who had been in Nova Scotia since 1749, was soon promoted to Lieutenant Colonel, and by 1754, the year of Lunenburg's founding and settlement was Lieutenant Governor of the province. Always a hard man and a stern disciplinarian, the extent of his increasing power and influence in the settling of the Acadian question lacked only the opportunity to prevail over both the Governor and the Lords of trade in London. But I digress.

From the original six families at Beaubassin the inhabitants of both the illage and surrounding district had increased and expanded over the years to, include many other families, all of which are recorded in the census of 1752, conducted after the people had foregathered across the Missaguash. Those inhabitants already established north of the river who were ranged westward round the head of the basin as far as Shepoudy, the Memramcook valley and other points across the isthmus, were scarcely affected by the exodus, at least not directly. Perhaps secure in the belief that they occupied French territory, they were undoubtedly accommodating in the re location of many among the displaced families, which included those from as far away as River Hebert and Menoudie.

In all, there were 43 family surnames comprising some 157 families that had been living at Beaubassin and throughout the Chignecto district south of the river. These, for the most part, were at Beausejour or in the vicinity at the time of the 1752 census. With Fort Lawrence constructed and manned by a British garrison, and having a clear view all round, it is highly unlikely that any of the inhabitants of Beaubassin village ever returned to salvage anything of value that may have been left, hidden or overlooked during the hurried departure in the spring of 1750.

Spring could be a cruel time of year in the region of the isthmus for people living in less than ideal circumstances, with cold north favoring winds and deep frosts, and always the threat of major snowfall. For most of the late winter the western district was virtually isolated from access by sea when the great, grinding dun colored ice pans choked the basin, being deposited on the mud bars by the ebbing tide, only to be repeatedly re floated and jammed into the narrowing channel by each succeeding flood.

Removing from the outlying settlements to Pointe Beausejour, hauling or carrying those necessities of life that could not be abandoned without jeopardizing survival, and driving what livestock was capable of making the trek, must have been an excruciating ordeal, coupled with the anguish of deserting, possibly forever, their homesteads of some sixty years. As disconcerting as the relocation must have been, the distances were relatively short and the new locale was similar if not altogether as familiar as the areas abandoned. Encouraging assurances by French authorities of security from political oppression and military harassment on lands considered part of New France undoubtedly created some measure of relief among the habitants, despite the upheaval. And always there remained the spark of hope that somehow the situation would be eased and they would be permitted to return. Nonetheless, within the framework of British intentions to exercise sovereignty over old Acadia officially and permanently re named Nova Scotia there were no concrete assurances that they even marginally accepted the boundaries claimed by France.

During several years following the construction of the three forts, a period of adjustment and hopeful, albeit vacillating, toleration between the two factions prevailed in the isthmus. The displaced people from south of the river slowly accustomed themselves to their new surroundings and, being mainly subsistence farmers, gradually overcame the initial hardship brought about by the relocation. In time a sizeable number of dwellings and outbuildings sprang up in the vicinity of Fort Beausejour and at Fort Gaspereau across the isthmus. At Fort Lawrence, above the crumbling ruins of Beaubassin village, the British garrison adopted the dreary routine of military life in an outpost that offered little in the way of entertainment and social diversity. The rank and file in particular faced the deadly drudgery of regular garrison duties. Trading in produce, livestock, game and firewood resumed between the habitants and the forts out of sheer necessity, including Fort Lawrence, where supplies were limited to the standard inventory, largely naval fare, of dried beans, peas, salt beef and ships' biscuit, delivered periodically by supply vessels, and through the organized enterprise of the garrison itself. Although LeLoutre had warned the people not to trade with the English, the only notable hostile action occasionally occurred between the Indians and the English, often resulting in the capture of work parties or woodcutters from Fort Lawrence by the Indians who, unlike the French, were perpetually at war with the British. In these events, the hostages were delivered up unharmed to the officials at Fort Beausejour for a bounty that was recovered from the British upon the repatriation of the prisoners.

While the former Beaubassin inhabitants at Pointe Beausejour could actually see the site where the ruins of their village moldered below the English fort across the marsh, those late of the other settlements south of the river could only remember their abandoned homes. Perhaps over time the longing for the old homesteads abated somewhat, the preoccupying effort to re settle and work new ground relieving the nostalgia. Undoubtedly the abandoned, once clean and cultivated fields grew weedy and overgrown and the uncut marsh grass thickened and matted, with the hay staddles falling as their posts were forced out of the ground by successive frosts. No other people moved on to the empty lands during those years, for the British had been slow to bring in immigrants of their own choosing, with those already arrived being concentrated in the Halifax, Lunenburg and eastern shore areas, and none at all in the Chignecto region, largely as a consequence of the unstable boundary situation. Nonetheless, by 1750, for the first time in the history of old Acadia, there were more English and English sponsored settlers in Nova Scotia than there were French, though not so widely dispersed.

Following the 1749 establishment of Halifax, British determination to demonstrate their sovereignty had intensified. To the French habitants something had gone out of old Acadia that would never be revived. In the old enclaves an uncertainty had entered into the laissez faire attitude that had prevailed for a century and a quarter. The people came to recognize their isolation and the lack of affective support from their countrymen. The British dominated the centers of population with strategic bastions and defensive works. They commanded the traditional routes and constructed new roads, joining sites and improving trails long established for communication among the widely dispersed habitations.

To the Acadians, their friends "the enemy" became less cordial, more distant and arrogant in their dealings. Although the people had bred and thrived almost entirely on their own over a span of two centuries, a new and ominous pall descended over the land, carrying a chill that was more penetrating than the relentless Fundy wind. Perhaps nothing could be more chilling to the people of Chignecto than the appointment of Charles Lawrence as Lieutenant Governor on 21 October 1754, following the recall of the relatively benign Governor Peregrine Hopson for health reasons. Lawrence, who had been challenged and humiliated at Beaubassin some four years earlier, was now in command. A staunch militarist, his mistrust of the loosely articulated Acadian neutrality, particularly their rejection of an unconditional oath of allegiance, rankled obsessively his military sensibilities.

To Lawrence a solution to the continuing Acadian intransigence was simple: Nova Scotia was a British possession. As such, its people were either British or British sponsored, and those not subjects of the British crown beforehand must necessarily swear an oath of allegiance in order to settle on British lands. History and tradition aside, the British were under no obligation to accept an oath that would exempt the people from defending British interests in time of war, and the Acadians had been, regardless of any other consideration, subjects of the British crown since the 1713 treaty. Even prior to any threat of expulsion the people had the option of removing to official French territory, to areas granted by the terms of the treaty that had handed old Acadia to the British for the final time, namely Isle Ste. Jean and Isle Royal Prince Edward Island and Cape Breton.

During the politically unsettled period 1750 55 a good number of Acadians did remove to the islands under the encouragement of Abbes LeLoutre and Maillard, some at a time when many in the British camp attempted to discourage the exodus for obvious reasons: their military were incapable of producing their own food supplies. In effect, part of the tradition that Charles Lawrence was prepared to forego was the Acadian willingness to supply the British garrisons and to trade as far afield as New England for the better part of a century.

Although officially at peace since 1748, war was never a distant option between the French and British crowns in Europe and particularly in North America, where open hostility lacked only sufficient provocation by one side or the other somewhere along the far flung frontiers of their respective territories. That provocation would be initiated in 1753 54 far from old Acadia, in the wilderness of Pennsylvania and the Ohio valley.

As with most military action, the combatants in a given sector see or know little of the overall picture, their perspective being restricted to what is observable. The civilian element, being ignorant of the broad strategic plan, are totally unable to fathom the source of, or the rationale for any action even when it affects them directly. Thus it was, in 1754, that a British contingent led by one George Washington challenged the French claim to territory near the confluence of the Ohio and Monbngahela rivers and, being beaten by superior French numbers, set in motion a series of decisions that would ultimately influence events in the distant Chignecto region.

While this and other frontier clashes were occurring, British colonial delegates were preparing the strategy that would be undertaken in the event of all out war, with pseudo defensive engagements aimed toward reducing French frontier forts and outposts. In this regard the decision was taken to remove the threat of such strong points as Fort Niagara and Fort Beausejour, in attacks led respectively by Governor William Shirley of Massachusetts who, in the move against Niagara was not successful, and by Lieutenant Colonel Robert Monckton. In the latter action, convinced that the French would reinforce Fort Beausejour in the event of open hostility, and use it as a staging area for incursions into Nova Scotia, Lieutenant Governor Lawrence decided that a pre emptive strike would serve to deny access to anyone attempting to supply Louisbourg via the traditional Chignecto routes, and to remove a dependable staging area for French troops despatched overland from Quebec. In this endeavor Governor Shirley assisted Lawrence by dispatching 2,000 colonial militiamen to bolster Monckton's 300 British regulars. Lawrence himself did not take part in the action. Beginning on 4 June 1755, this combined British force laid siege to Fort Beausejour.

At the time, the French had some 1,400 men in the region of the isthmus not all soldiers or members of a dependable militia. At the fort were 165 regulars and their officers and about 300 Acadian volunteers. Ordnance amounted to 21 guns and one mortar. Although prior knowledge of the British build up at Boston and Annapolis Royal had reached the fort, via the moccasin telegraph, as well as news of the British capture of a supply vessel from Louisbourg en route to the Saint John River post, there was little time to bolster the neglected defenses of Fort Beausejour. Too long secure in the belief that occupying territory assumed to be French, with Britain and France ostensibly at peace, the defenses at the fort had been allowed to gradually deteriorate to the point where, as future wars would prove, even the most up to date fortress defenses could not sustain a protracted siege, never mind a fort so sorely neglected. In the circumstances, at Beausejour the only recourse was to defend until the battlements were reduced to rubble. Fortunately for all concerned the situation there never progressed that far.

At 5 a.m. on 2 June the fort was informed of a British fleet of some 41 sail lying at anchor behind Cape Maringouin, off the Shepoudy shore, awaiting the tide to enter the great looping channel of the upper basin. The Commandant at the fort, Captain Louis du Pont Duchambon de Vergor, desperately despatched couriers to Louisbourg, the Saint John post, and other enclaves throughout the region, and as far away as Quebec, begging for assistance.

At 5:30 in the afternoon the British ships closed on the estuary at Beaubassin, with the escorts anchoring in the stream while the transports and supply vessels were moored ashore along the broad, tide swollen LaPlanche and Missaguash riverbanks at the place where Jacques Bourgeois and his party had landed alone and unchallenged some 83 years before.

The landing ground at the confluence of the two rivers is remarkably unaltered in the modern era, with the exception of the river mouths now meeting the common channel to the basin somewhat nearer the shore. The ground a short distance east of the estuary rises gently above the marsh to the south and is largely unaltered. It comprises a low hillock that gradually descends eastward to the site of Beaubassin village, with the ground then rising again to the high ground above the toe of the ridge, where Fort Lawrence had been constructed.

Throughout the early summer evening, troops and supplies were off loaded while the tide was at its peak, a height that over the next six hours gradually lowered until the vessels were careened in the bed of the streams some forty feet below the upper shore. Nonetheless, tents and accommodation stores were hurriedly discharged and hastily assembled. With over 2,000 men working into the twilight, hundreds of tents in two precisely dressed lines soon occupied the broad field on the flank of the ridge, below Fort Lawrence.

Although much of the activity at Fort Lawrence was easily observable by the French at Fort Beausejour over the next few days, the preparation open to them in the face of the looming action was meagre indeed. Men and supplies of food could be brought inside the fort, but it was too late to establish and man effective field works beyond the perimeter in order to stand the British force off beyond gun range. As well, the virtual Acadian village that had sprung up in the vicinity of the fort over the past five years some 60 odd buildings was a liability to defending the immediate area surrounding the fort.

On the morning of 4 June the British tents were struck and the troops assembled. The French knew that it was imperative for the British force to march to an adequate river crossing site, which could not be contemplated anywhere along the broad, deep and muddy banks of the Missaguash over the first few miles upstream. The French also knew where that site would be, and made hasty, albeit futile preparations. The first viable river-crossing site was at Pont o Buot, about five miles east of Fort Beausejour, where the habitants had erected a bridge, one that was well known to the British garrison at Fort Lawrence. Needless to say that by the time the British column reached Pont o Buot the bridge had been burned and the French were ensconced in the log blockhouse and along the edge of the woods on the north side of the river, half heartedly determined to slow the British crossing.

British sappers, utilizing bridging material they had brought with them, set about constructing an improvised structure to replace the one burned by the French, at which time fire was directed across the river from the line of woods, with several small swivel guns firing from the blockhouse. The British retaliated with concentrated fire from four brass six pounder guns, which had been laboriously hauled from the Fort Lawrence encampment. These quickly neutralized the French guns and drove the Indians and civilian volunteers out of their firing positions, leaving only a few French regulars in the trenches. For whatever reason, the guns were removed from the stockade and hauled away in a cart, to be sunk in a bog. Spiking or bursting them in situ would have been infinitely easier, while hauling them all the way to Fort Beausejour would have been less wasteful.

While the British labored to complete the bridge, the French officers ordered all stores to be removed from the storehouse and all buildings, including dwellings in the vicinity, to be set afire. The remainder of the day was taken up salvaging what could be hauled away, and on the following day the settlers at Pont o Buot and those who had defended the bridge site moved into the fort.

By the evening of 5 June the entire British contingent were in temporary camp on the north side of the river. For the next couple of days they consolidated their foothold and cleared the area for tents and storage areas. Heavy stores and equipment were transported upriver in supply vessels on the running tide and westerly wind without incident, and another bridge was erected farther downstream to expedite communication with Fort Lawrence. With the elimination of French resistance at Pont oBuot, reconnaissance was conducted to ascertain the best location for the heavy uns and entrenchments in the vicinity of the French fort, and by the IOt construction of a road over which to transport the heavy siege guns was commenced. By then a site for the gun emplacements had been selected on a rise of ground to the north of the fort, and the sappers, under cover of night, had carried the entrenchments to within 700 feet of the ramparts.

In the meantime the French had removed supplies and other salvable material from the dwellings near the fort and burned the buildings, once again displacing the inhabitants. They offered a cursory response to the British occupation of the ground selected for their guns by sending out skirmishers and firing a few gunshots from the fort. In the short action first blood was shed, with one man on the British side killed and a half dozen wounded before the overwhelming British force of 500 men drove the French off.

Overcrowded conditions inside the fort lent little encouragement to the already demoralized defenders. The order to raze the surrounding buildings prompted those Acadians not involved with the defense to salvage as much of their portable property as possible, leaving the task of repairing the fortifications and replacing weathered fascines in the earthworks woefully neglected. The Commander, a dull, stuttering, uneducated man, had little heart for a fight with the superior British force. Many of the Acadian men who had previously volunteered to defend the fort opted to move their families into the woods, out of harm's way, rather than expose them to danger in the dubious security of the fort. As well, many, of them, having encountered the British first hand at Pont o Buot petitioned the Commander to be allowed to fight in their own way in effect, to relinquish the confinement of the fort for freedom of movement in the woods.

All in all, faced by a vastly superior force that was evidently intent upon a protracted siege, the French authorities lacked only an honorable excuse to capitulate. That came on 16 June, 12 days after the British Force disembarked at Beaubassin.

To say that the French garrison held out for 12 days is not to imply that they did so through any protracted or heroic resistance. Aside from some desultory gunfire aimed at the British sappers engaged in digging and constructing entrenchments and gun emplacements within effective range of the fort, the French regulars and the reluctantly recruited Acadians grudgingly acknowledged their lack of essential fortitude, if not the means for countering the British blockade.

During the largely unopposed advancement of the British trenches under cover of darkness, a heavy, 13-inch siege mortar was moved up within effective range of the fort. On 16 June a single round of explosive shot was lobbed into the fort. This projectile, a hollow iron sphere filled with gunpowder was exploded by a length of fuse inserted through a small, tarred hole in the shell casing. Depending upon the range to the target, the propellant charge was measured and the fuse cut to a prescribed length. Upon firing, the fuse was ignited by the propellant charge and burned during the flight of the projectile. If all of the calculations were correct, the fuse burned into the interior charge of the shell and exploded it when the target was struck. While discrepancies in range estimation and propellant charge might cause the shell to explode slightly before or after first strike, the effect of the explosion was little altered by the difference. In the case of the fateful shell of 16 June 1755, the precision of the gunners' calculations was bang on the money.

While the Abbé LeLoutre and Commandant de Vergor sat in one of the two bombproof shelters, the mortar shell landed beside the entryway of the other before exploding. The explosion and shower of iron fragments penetrated the interior, killing four men, one a British officer prisoner, and wounding another. The response was immediate. De Vergor dispatched an emissary under a white flag to negotiate a cease-fire. LeLoutre, having proclaimed to the Acadians that it would be more honorable to die in the ruins of the fort than surrender to the despised British, made his own preparations for avoiding certain British retribution for his clandestine activities. While the terms for an honorable capitulation of the garrison were being negotiated, Abbé LeLoutre, in the disguise of an Acadian woman, made his escape, betraying and abandoning both the God fearing habitants and his loyal Indians. Managing to make his way overland to the Saint John River post, he subsequently journeyed to Quebec, where he was received with little attention or interest, embarking shortly thereafter for France, never to return to North America. Thus ended an ignominious reign of hate spawned fear mongering that had served at most to alienate the British against a benign, unthreatening people who were systematically manipulated through their peasant fear of religious retribution and the sword of Indian brutality that LeLoutre held over them.

The terms of capitulation, although they might have been unconditional from the British point of view, were sufficiently generous to satisfy the requirements of the event and also preserve the honor of the French garrison. The British took possession of the fort at 7:30 in the evening. Following the signing of surrender terms, Captain de Vergor laid on supper for the French and British officers, and on the following morning the garrison were permitted to march out of the fort with their arms and baggage. They were subsequently placed on board one of the transport vessels, along with an appropriate guard, to be transported to Louisbourg via the Bay of Fundy. One of the terms of capitulation granted that the Acadians found inside the fort would be released without retribution. This was brought about by a signed petition stating that the Acadians had been forced to take up arms in defense of the fort. Although as fair and innocuous as this release from responsibility might have appeared, in the mind of Lieutenant Governor Lawrence it exemplified the hollow nature of the Acadian insistence upon the clause of neutrality in the oath of allegiance. It was a fateful concession that would soon resurface to the Acadians' peril.

The final consolidation of the isthmus called for the reduction of Fort Gaspereau at Baie Verte, to which end a detachment consisting of Colonel Winslow and 500 men was dispatched at 11:00 a.m. on 18 June. Arriving at the fort at sunset they entered and took possession, unopposed by the Commander, M. Vilray, about 30 regulars and a few artificers. Perhaps as a result of the same apathy that had left Beausejour defensively deficient, the situation at Gaspereau was deplorable, with no well, few of the daily necessities of life and the fort itself in a poor state of readiness.

After securing the fort, 200 men were despatched to inspect and secure the village of Baie Verte, which they had passed through on their march to the fort. The village contained about 25 dwellings of sound quality, a church and a priests' house. The apparent prosperity had resulted from the villagers' traditional role in trading with the settlements on Isle St. Jean and Louisburg. Although Winslow was of a mind to abandon Fort Gaspereau, in light of both its general condition and strategic location, Colonel Monckton took a contrary view, ordering Winslow to return to Beausejour escorting the French garrison, which he did on 23 June. Monckton then dispatched a fresh detachment of 200 men under Captain Thomas Speakman to improve the fort, which was subsequently renamed Fort Monckton.

Also on 23 June, Captain John Rous, Commander of the combined British naval group, sailed from the Beaubassin landing ground with three 20 gun frigates and a sloop, in company with the transports bearing the French garrisons of both forts to Louisbourg, and a British force intent upon the reduction of the Saint John River post. With the fleet's arrival off the mouth of the river, on 30 June, the forewarned French garrison burst their cannon, exploded their powder magazine and fled upriver.

At the isthmus, as early as it was expedient, the British moved the garrison and headquarters from Fort Lawrence to Beausejour, renaming it Fort Cumberland, thus extending their claim beyond the boundary of old Acadia into the disputed territory, while having effectively removed French military presence from mainland Nova Scotia.

Whatever hope for the security of their situation north of the Missaguash the people at Chignecto may have nurtured during the five years since the abandonment of Beaubassin, they now faced the reality of once again being entirely on their own in British occupied territory. It must also have appeared that any notion of a boundary separating French from English was redundant. Seeing Fort Lawrence so hastily abandoned in favor of the more soundly constructed Beausejour, and being free of the threats of LeLoutre and his Indians, it should not have required a giant leap to hope that the conquerors might even consider their return to Beaubassin and the satellite settlements south of the river.

Nonetheless, when viewed from the perspective of those Acadians in the immediate vicinity of the forts, who were again uprooted during the short, one sided conflict, the future must have appeared grim at best; surely predictive of an uncertain period, with virtually nowhere to turn for advice and direction except to the very people who were the root source of their predicament: the English.

Abbé LeLoutre was gone, and aside from the danger the people saw in him, based on his manipulative bullying and their fear of his Indians, he had represented their best source of guidance for the uneducated, and a broader point of view for the motivated among them. Unfortunately his consuming hatred of the English had compelled him to wield the Sword of Damocles in order to counter the trusting, unassuming temperament so deeply rooted in the Acadian character, a disposition that saw them extremely naive even in their dealings with those who would be their enemy.

What must have become increasingly apparent was the question of the oath of allegiance. Certainly it should have been clear to the people in the Chignecto region unlike the other centers in Nova Scotia where the habitants had yet to witness British military efficiency in action that vying for neutrality, or any other condition short of total allegiance, would be futile.

In the aftermath of history what had come to pass, beginning in the summer of 1755, is open to analysis from many points of view. The chain of events following the surrender of Fort Beausejour was set in motion by the very requirements for the conduct of the siege: a military force, requisitioned transports, and armed escort vessels. With the cessation of hostilities and the removal of all threat of counterattack, having suffered virtually no casualties, It must have occurred to Lieutenant Governor Lawrence that he had at hand a combined ground force of some 2,500 men and a collection of transport vessels with nothing to do. He also knew that he had the sanction of Governor Shirley for their mutual plan, and that delay might mean failure should Shirley, on the pretext of dire need, call for the return to Boston of his militiamen, although a further ten months remained of their contract. In the circumstances Lawrence countenanced no delay.